I used to think that I was fighting a losing battle…

Where it began

I first encountered different learning theories while studying for my Master’s Degree at Hanoi University in 2015. These theories not only answered my burning questions about teaching, but also address how changes in students’ observable behavior become relatively permanent, and what role experience and reinforcement plays in making those changes (Olsen & Hergenhahn, 2013).

After receiving my degree, I continued teaching classes of Vietnamese EFL students who aimed to take the IELTS test.

Then, in 2018, I started working as a product developer for IEG Global – an educational organization based in Hanoi, Vietnam. In the first few training sessions I received at IEG, the concepts of 21st century skills and contemporary pedagogies were once again discussed and instilled in my teaching and product-designing mindset. Ever since then, I have always tried to adjust my teaching styles and materials in order to pursue the goal of sustainable education and innovative learning, no matter in my private classes at home or my larger classes at various English centers.

Growing up, I have been heavily influenced by the traditional learning approaches in Vietnam and had to rediscover active and independent learning approaches through years of trials and failures. Therefore, I yearn to incorporate the contemporary views of constructivism and experiential learning into my teaching and wish that those changes could aid my students in pursuing their highest educational goals.

A reflect on the traditional lecture-based teaching in Vietnam

There are three main difficulties that I have encountered while attempting to apply seemingly innovative and sustainable approaches in my teaching.

Firstly, students in Vietnam are not usually encouraged to find their own learning paths, let alone discuss and question what their teachers are teaching. Meanwhile, Vietnamese teachers are often held on the pedestal and considered to be the fountain of knowledge or the center of a classroom. In my experience, if I cannot immediately provide answers to students’ questions, I would often be deem incompetent or unprofessional. Therefore, it is really challenging to guide my students on how to look for answers by themselves, how to be critical with what they find, and most importantly, how to make essential questions instead of matter-of-fact ones. Even though I strongly believe in what Sönke Ahrens reinstated in his book that both the teacher and students are in the classroom not for each other, but to find the truth (Ahrens, 2017), I was not respected for admitting that I did not know something.

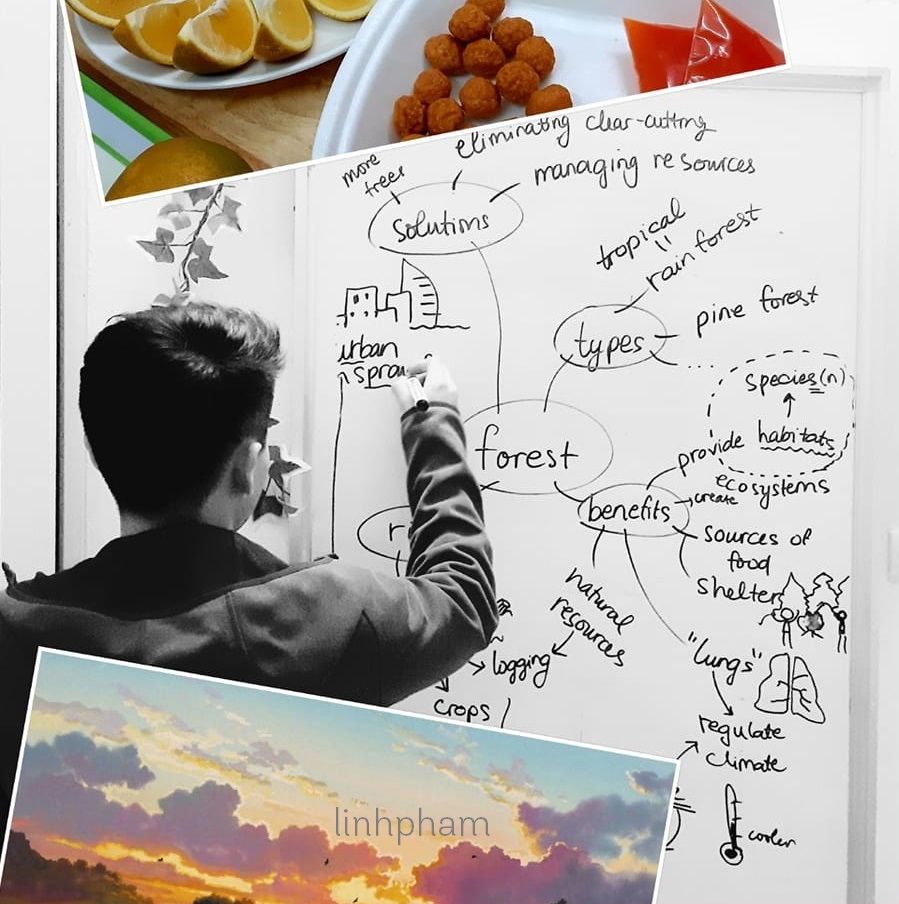

Secondly, many modern or Western-based pedagogical concepts such as collaborative learning or 21st century skills are wildly and hastily applied in Vietnam due to ‘false universalism (the belief that a practice that originated from elsewhere can be “cloned” with similar results)’ (Nguyen, Terlouw, Pilot, 2012). From my own high school and university experience, many teachers seemed to love group discussion activities or mind mapping exercises. However, simply forcing students into groups does not equal facilitating collaboration among the group members. And apparently, making students create colorful mind maps without proper instructions does not boost their creativity but inflicts resentment instead.

And lastly, a large number of students in Vietnam do not really know how to learn effectively. To them, learning is torture and uncomfort. And any indication of the love for learning could gather more laughter than sympathy.

Simply put, as an English teacher who only meets these students once or twice a week, it is almost impossible for me to implicate any significant changes in their learning styles. These are the reasons why while what I could impact during my 10-year-teaching-journey does sometimes seem like fighting a losing battle.

A promise

Since I first got my teaching job in 2013, IELTS has bypassed TOEFL to become the most popular standardized test in Vietnam. Now, the “IELTS-industry” in Vietnam is a brutal place for both well-wishing teachers and oblivious students.

Many IELTS centers only care about profits. And a lot of students just want to achieve their targeted band score without studying English. Language proficiency and comprehension is not even their first aim, let alone learning skills like critical thinking, creativity, collaboration and communication.

During those 7 years of teaching IELTS courses (since 2013), my students were still able to achieve their targeted band scores. However, no matter how hard I tried to integrate what I consider more sustainable than test-taking skills into my teaching, I still felt like I could not change anything.

After trying in vain to convince parents and students to take time acquiring English before jumping into preparing for the test, I could only promise myself that good things take time.

What I have done

I put every ounce of energy I had into carrying out the following three tasks:

- Build a personal brand. If I could not convince Vietnamese parents and students with my credentials nor with class activities and students’ performance, ironically, I have to become somewhat of an influence. I started making Youtube videos in 2015 and gradually build a learning community there. In 2020, finally I had the chance to speak openly about the IELTS test and the myths surrounding it. And this time, more people listened.

- Learn. Learn. Learn! Only when I am more knowledgable of the different teaching and learning approaches, could I be more confident in applying them.

- While maintaining my effort in integrating these more sustainable skills in my lessons, at the same time, I have to respect my students’ individual goals.

Crititcal thinking

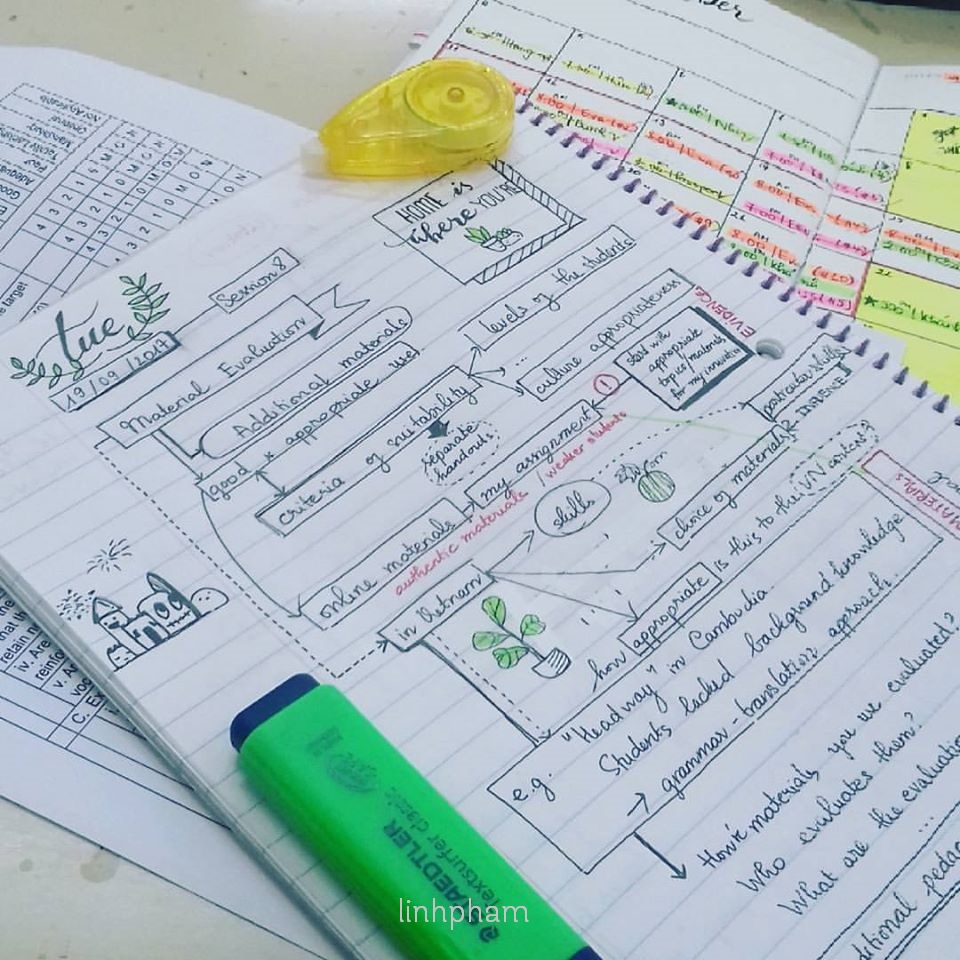

I have come to realize that the only way I can encourage my students to ask questions is to simply welcome them. When it is time for questioning, I always visualize my students’ ideas onto a large surface so that every student in the class could all look into the problems and think for themselves.

It is inspiring to witness students gradually transform themselves from not being able to raise their voice in class to tentatively ask questions, and then to confidently challenge my assumptions.

Creativity

“The heart of creativity is discipline.” William Bernbach

I believe that careful scaffolding and clear instructions are far more effective in boosting students’ creativity than simply giving them “freedom”.

Only when students feel safe to express themselves, they could be free to tap into their inner creativity (Golinkoff & Hirsh-Pasek, 2016).

Collaboration

Collaboration is not a simple skill to teach. Many Vietnamese students detest group-based projects at school because while they are expected to be flexible and helpful in working with their peers (The Pacific Policy Research Center, 2010), many team members seem to lack enthusiasm and often not contribute to the team’s work. The responsibility for collaborative work more often than not falls onto a few members who are willing to work, and the workload in these cases are not distributed fairly. If I want my students to collaborate, I have to make sure that these issues are addressed.

Communication

Doctor Chi Hieu Nguyen, CEO of my company always stresses the importance of communication. In order to help students communicate openly and effectively, we as teachers have to be their leading example in delivering our thoughts, emotions and beliefs.

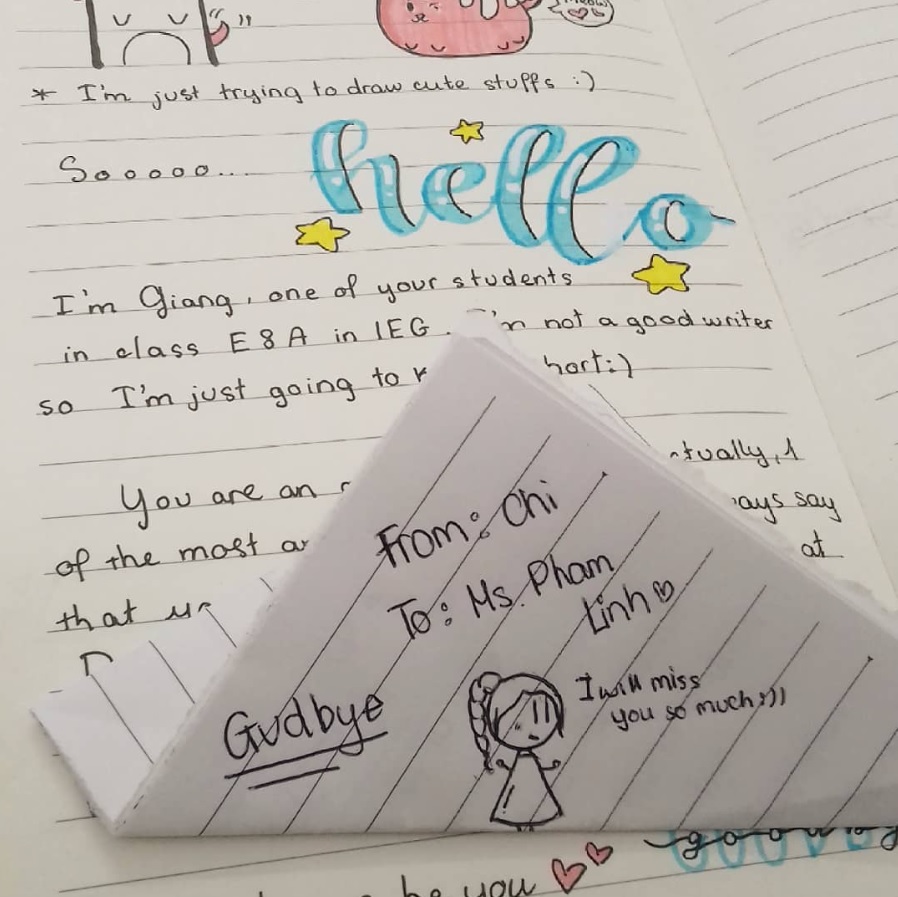

Once again, I find active listening with mutual respect to be the most effective when it comes to help my students build trust. As long as I can listen to them without prejudice or judgement, they would listen to me and to each other and be open to share.

Many of my former students later told me that they did not remember much of the test-taking skills that I taught them during class, but they would forever appreciate how I was always willing to listen to their problems and patiently guide them to find the answers.

Listening, trully listening, seems to be the great first step of fostering critical, creative and collaborative minds.

Harnessing technology for collaborative learning

When Covid-19 hit Vietnam, all of my classes had to resume into online mode.

“How can I maintain the value of my lessons and engage students in class activities even when we lack the environment of a physical classroom?” I often asked myself this question after every online session we had.

After several weeks of trying to stay connected with my students via different online platforms, I decided to take some courses about effective online teaching and remodel the way I teach.

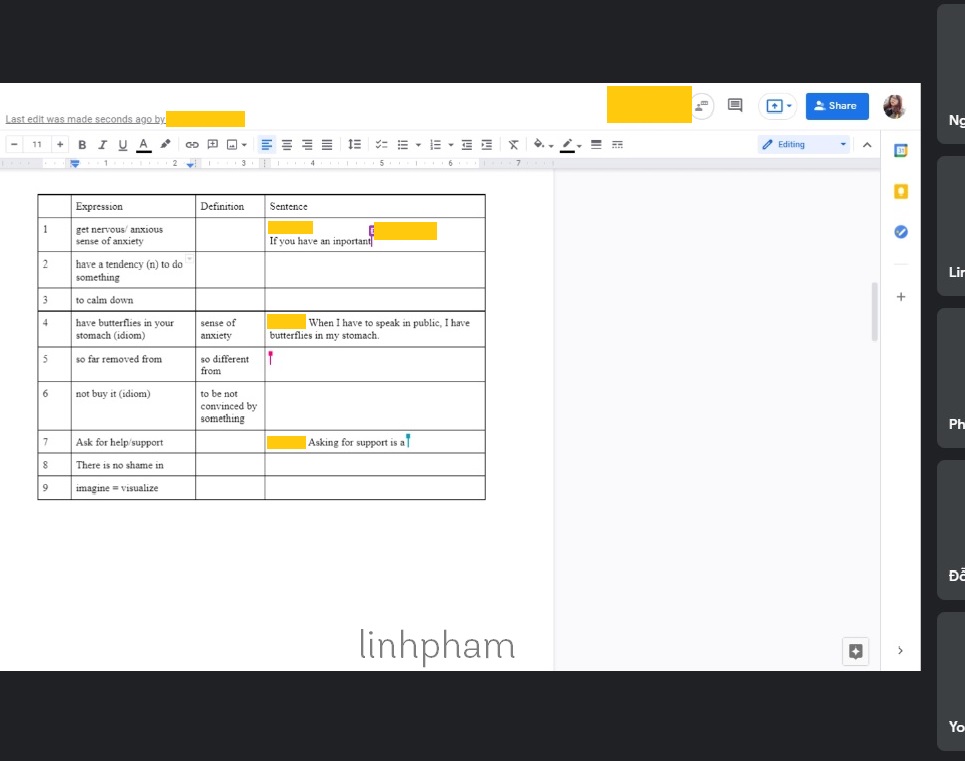

I started to fully utilize Google’s free tools like Google Meet, Drive, Doc and Jam Board to connect with my students. Once they realized that they can interact with each other freely on the same platform at the same time, the rest is history.

My students are now confident in using technology to collaborate and communicate. They even discovered new ways of learning and constructing ideas thanks to technology.

Embracing the journey

Eventually, I quit teaching test-oriented classes.

The last 3 years of transitting from traditional classroom to online teaching, and from teaching-to-the-test to trully teaching English, to me are blessings in disguise. Looking back, I did better than I had expected. And to be frank, the way I used to treat my effort was not sustainable nor healthy.

I now realize that as long as I have clear vision of sustainable and innovative teaching in mind, I can keep going even when things are tough.

“The fact that you worry about being a good teacher, means that you already are one.” – Jodi Picoult

References

Ahrens, S. (2017). How to Take Smart Notes: One Simple Technique to Boost Writing, Learning and Thinking for Students, Academics and Nonfiction Book Writers.

Nguyen, P.M., Terlouw, C. & Pilot, A. (2012): Cooperative Learning in Vietnam and the West–East educational transfer, Asia Pacific Journal of Education, 32:2, 137-152. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02188791.2012.685233

Golinkoff, R. M., & Hirsh-Pasek, K. (2016). Becoming brilliant: What science tells us about raising successful children. American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/14917-000

Olsen, M. & Hergenhahn, B. (2013). An Introduction to Theories of Learning (9th ed.) Pearson.

Pacific Policy Research Center. (2010). 21st Century Skills for Students and Teachers. Honolulu: Kamehameha Schools, Research & Evaluation Division.